Shelly (Shell for short), was fired for immoral conduct. Basically, she wouldn’t let a disabled person onto her train. It had nothing to do with his wheelchair – the guy had been inebriated, intoxicated, and abusive. But try making the bosses listen when all the spectator recording the incident on a mobile phone had filmed was her telling him to get lost, go away, because there was no way he was getting on. It was broadcast on Granada Tonight, and, as a result, she would never work for any rail company in the country, ever again.

She couldn’t apply for any transport job, for that matter.

Being a train expert, what she loved most in all the world to do was drive trains. To take that away from her spelled trouble. Shell lived alone, and still had a vintage train set from childhood elevated in the spare bedroom. She spotted trains, when she wasn’t working. A lot more so, now.

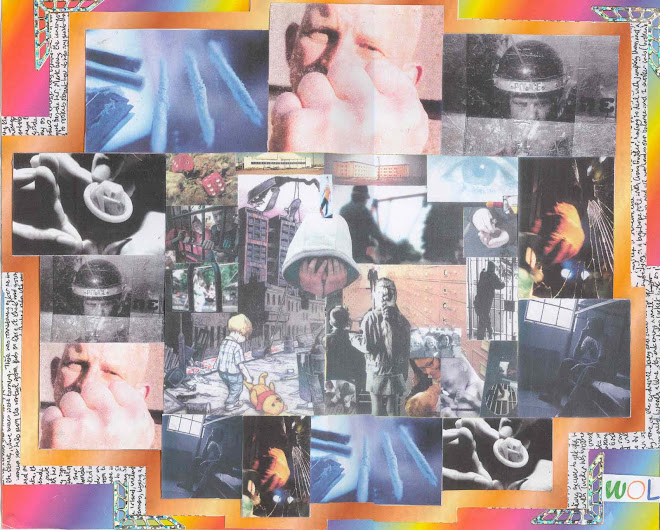

What made her get fired up enough to hijack a lead carriage from Liverpool Lime Street Station, and thrust it full throttle towards Manchester Piccadilly, was a mix of situations and circumstances, mostly involving social life and finance, fuelled by drugs. She had never been a drug user, and experienced an acute psychotic reaction.

As soon as she was in motion, she negotiated the terms over the radio. She was to speed from Liverpool to Manchester in a single carriage, without any halt, disruption, or line changes of any description. If anything tried to stop her, herself and the hostages (which she had convinced them into believing she had) would die.

As soon as she reached maximum overdrive, at over 150 miles per hour, Shell took herself into the small seating area, handcuffed herself to a passenger rail, and slumped to the floor. She could see through the glass doors, and still hear the radio spitting the crackly negotiator’s voice. Her ears morphed the voice into one she recognised, from a romantic yesteryear.

In her vision, she created a body for the voice to speak through; a young man from her youth, who she had dated but once. He kicked at the rail she was attached to, trying to free her, and pulled at the cuffs. She whimpered at the pain in her wrists.

It had been over thirty years since Shell’s last imaginary friend. With the drugs in her system, her imagination had assumed a power beyond her control. Her make-believe partner in her empty carriage was almost tangible before her very eyes. She could actually see his details, if she squinted. His brow, his hairline, the veins in his neck.

He seethed and huffed, shouting and cursing, kicking and pulling the pole attached from floor to roof, but there was no budging it. Eventually, defeated, he sat down next to her.

The city architecture and the surrounding borough of Tetris-like terraced houses had flickered by in an instant and now the carriage was already into her hometown, whizzing by her old school.

A tear from each eye rolled down each cheek. “You go,” she said. “Jump.”

He shook his head and embraced her. “I don’t want to live if I can’t live with you.”

“You have to save yourself. If you jump, you’ll live. That’s the way it is. Your bones will heal.”

“My heart won’t.” Her imaginary friend, and imaginary lover, snuggled closer. Together, they embraced.

And that embracing, coupled with the speed, is what it was all about, in Shell’s world. That fusing into his flesh, that contact of his being....wonderful. Every other problem, worry and care had no other option but to rush by on the wind, like semi-transparent ideas over white, foamy rapids; distant, fading, unimportant.

Life was all about poignant, touching, empathic moments. To wrap death up in such a few and far between moment was like a fairytale ending to a mundane documentary.

The landscape blurred into a wash of buildings and sunset. That line in the sky dividing night and day is called the terminator shadow*, and it was the only thing that could keep up with them.

The carriage hurled into Manchester Piccadilly stations and ejected off the rail like a car flipped off a ramp, skidding through a perimeter fence, down an embankment, and into the city itself, colliding with stationary traffic.

Shell died with the versatile elasticity of her imagination intact.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

Yes, Taz is still getting chonged, and no, Taz hasn’t yet wrote the sequel to her breakthrough story, Moon Rabbit. She is still singing along however to her good friend Roy’s guitar and once even recorded her good self, Roy, and DB Tinkerbell in her flat. If that tape can be found, it will be uploaded to the quasarboy77 YouTube channel in the future.

*visible on any clear sunset by lying on your back and looking up behind your head

Wednesday, 1 December 2010

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment